“As long as you speak my name, I shall live forever.” — African proverb.

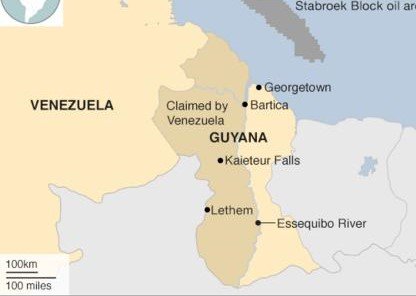

In the midst of the current controversy in the United Kingdom surrounding the pedophilic revelations about Prince Andrew (now Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor) and his links to Jeffrey Epstein, communities there are demanding his name be removed from public spaces. This made me reflect on our own situation in the Caribbean, where centuries after European enslavement and genocide, our national landscapes remain cartographies of colonial power. Many of these historic figures have committed crimes that were evidently as bad or far worse than the known crimes of Andrew Windsor.

Colonial Symbols Inflict Continuing Trauma

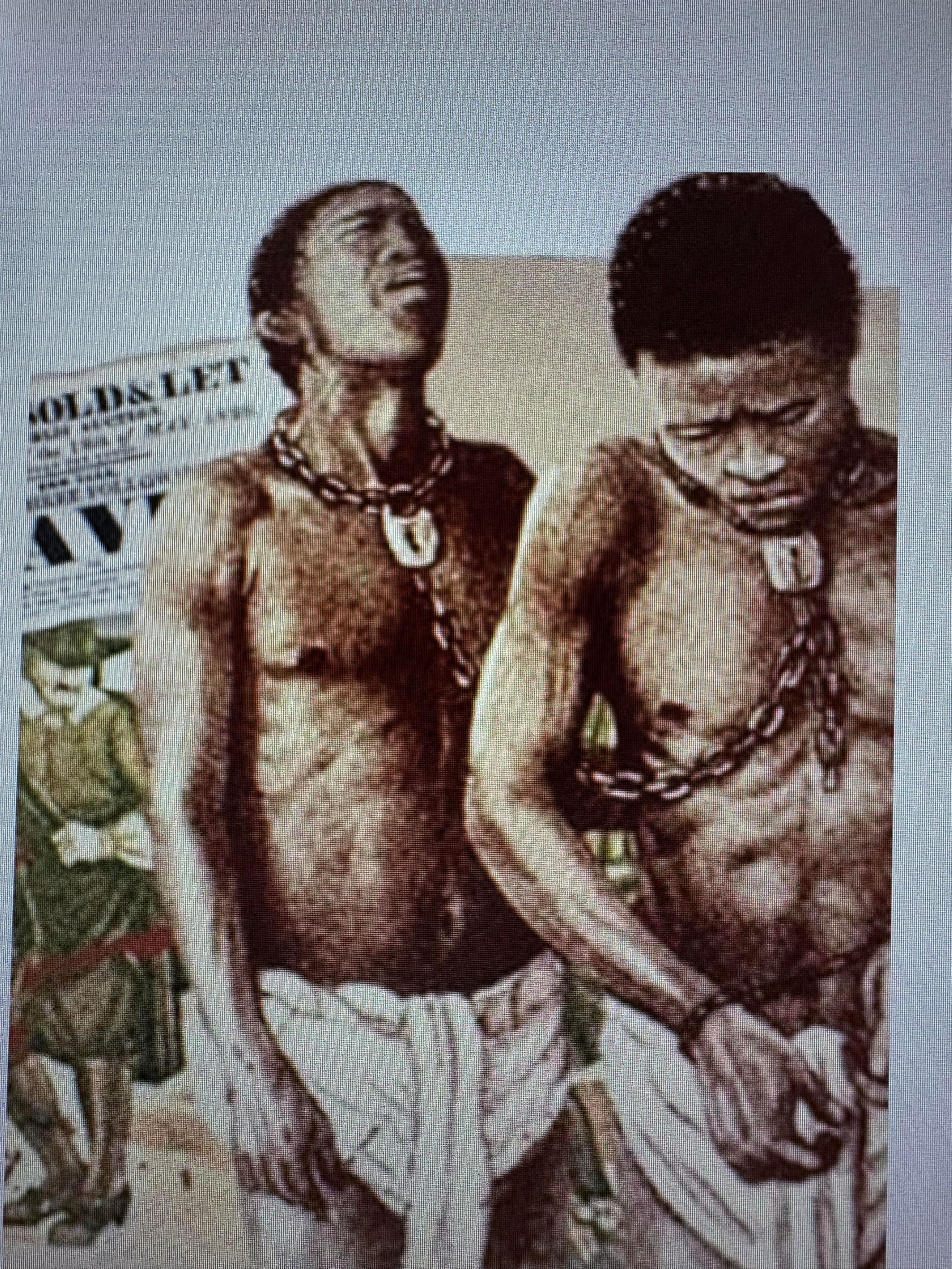

Yet, from capitals to public streets, the names of enslavers, including monarchs and their heirs, colonial administrators, and other colonial enforcers, litter our commons. For many with basic historical awareness, these names are constant reminders of injustice, violence, and subjugation. Research helps us understand why this daily encounter with colonial symbols is more than a nuisance. Studies in psychogeography as well as intergenerational trauma reveal that constant exposure to the names, images, and other monuments of oppressors can inflict psychic trauma. In a similar context, Dr Joy DeGruy terms such persistent, subtle, and chronic psychological harm “insidious trauma.” When the only “heroes” celebrated are the enslavers of our ancestors, we are left inhabiting a psychological landscape of subjugation and pain, further cementing institutionalized racism and psychic injury.

Correcting this imbalance is not about rewriting our past, it is about reclaiming our present. It is about instilling future generations’ pride in their heritage and inspiring them through stories of courage, intellect, and resilience. Just as the Steel Pan transformed waste into harmony, so too we can transform the remnants of colonialism into symbols of Caribbean strength, memory, and hope.

Resistance and Reclaiming Our Heritage

The United Nations Second International Decade for People of African Descent (2025–2034), under the theme “Recognition, Justice, and Development,” offers an urgent and fitting context for this reckoning. This international focus presents an opportunity for Grenada and other Caribbean nations to deepen the conversation about honoring our indigenous and African-descended heroes.

It is also one in which we can seek to advance the cry for justice for crimes committed against our ancestors and its continuing legacy of colonial baggage. The Development aspect of the 2nd Decade’s theme can be interpreted to mean reclaiming our sovereign spaces — mentally, culturally, and physically. Also relevant is the Caricom Reparations Commission’s 10 Points and its appeal to our governments for the removal of all statues and memorials dedicated to colonizers and enslavers as part of its broader advocacy for reparative justice.

With regards to justice, a cue can be taken from a 2020 UK court case following the toppling of enslavers’ statues. A defense in a particular case was allowed the argument that the statue’s presence can constitute a “hate” crime. And that “reasonable force” can be used to remove monuments, such as Edward Colston’s. The defendants were acquitted of criminal charges. In our Caribbean reality, reasonable force could mean deliberate, democratic action — government policy shaped by the will of the people.

On May 22, 2020, young activists in French-colonized Martinique tore down two statues of Victor Schoelcher to highlight that, on that same date in 1848, the enslaved had freed themselves rather than wait for the French administration and Schoelcher to grant their liberty. Two young women publicly accepted responsibility, explaining that the venerated Schoelcher was not their savior and calling attention to ongoing injustices. Still, their actions drew harsh criticism from local leaders, intellectuals, and even President Macron. But their action has popular support from the Martinique working class and youth. Their trial is upcoming.

Though Caribbean nations like Grenada proudly celebrate their independence, with their own flags flying high, the lingering presence of colonialism is still etched into the landscapes through the names of streets, buildings, and monuments revering enslavers and colonial administrators. These “colonial flags” remain planted in everyday geography, reminding us of the coercion once imposed by imperial powers.

Even institutions like the ‘Royal’ Grenada Police, His Majesty Prisons, Princess Alice Hospital, Fort George, and Sendall Tunnel, for example, carry the imprints of that unfortunate past. The appeal to rename these public spaces is not merely about changing labels — it is acts of resistance, reclaiming identity, and reshaping national consciousness and national conversations. This need to redress and address our cultural memory should be even more urgent after new research reveals various British institutions, including the Church of England, and King George IV profited from slavery in Grenada. This should make one question the virtue of maintaining our capital and other geographic spaces with all references to George.

Self-Determination is Nation-Building

If, as many specialists have maintained, the persistence of these colonial symbols can trigger post-traumatic stress, then their removal and replacement may foster positive psychological results, such as national pride, and an appreciation of positive local role models. As a result, collective healing can emerge when pain and the absence of historical triggers are transformed into empowerment. Nation-building acts such as renaming our streets and honoring our own heroes can reshape our collective identity and improve psychological well-being. It can validate cultural worth, nurture pride and self-determination, and foster development.

Renaming is beyond symbolism; it is psychological liberation. When we replace these colonial and enslavers’ names with those of our ancestors, we change the rhythm of our daily lives. We walk in the footsteps of those who loved freedom and justice as much as life itself. As we re-tune the soundscape of our societies, we turn dissonance into the harmony of Big Drum rhythms and Nation Dance.

Like the steel drums born from resistance and creativity amid oppression, let us project a Caribbean that is a living symbol of unity forged through struggle; reimagine the discarded relics of colonial shackles.

Martin P. Felix is adjunct professor of Caribbean Studies and coordinator of the Caribbean Studies Minor, Department of Social Sciences, at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), State University of New York.

Share with your network