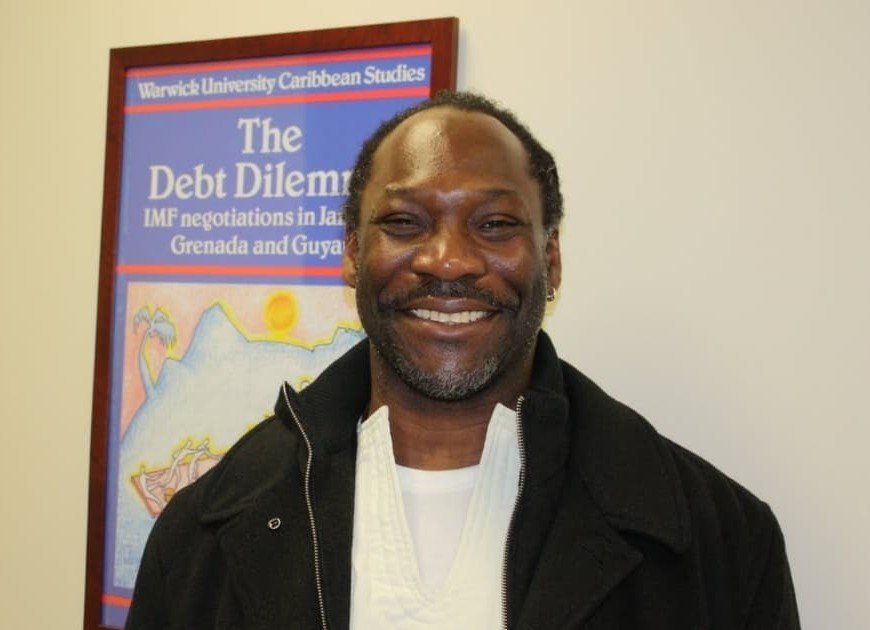

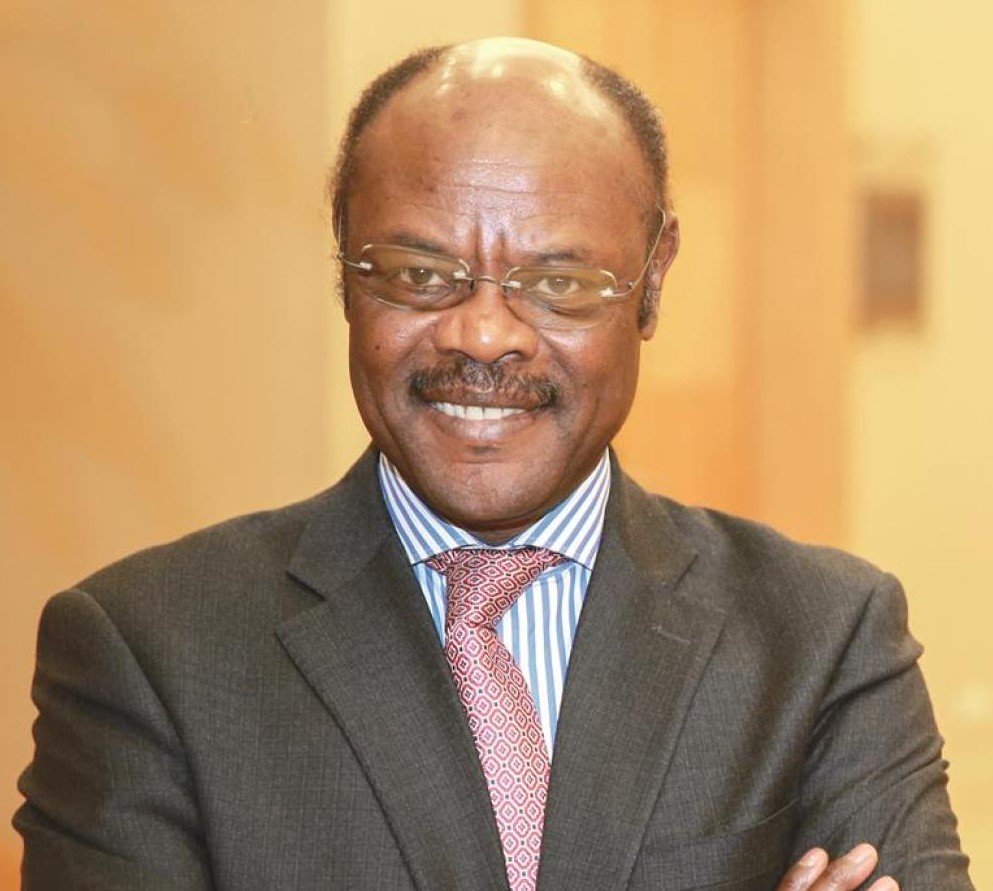

Recently, the St. Paul’s Church in the Village of Flatbush in Brooklyn, held a two-day International Homecoming, which addressed the role of the church in the enslavement of Africans; the theme of the event was: Justice, Reconciliation, and Repair: Confronting our History. The guest speaker was Professor Martin Felix, adjunct professor of Caribbean Studies and coordinator of the Caribbean Studies Minor, Department of Social Sciences, at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), State University of New York. The following are excerpts from Prof. Felix’s presentation:

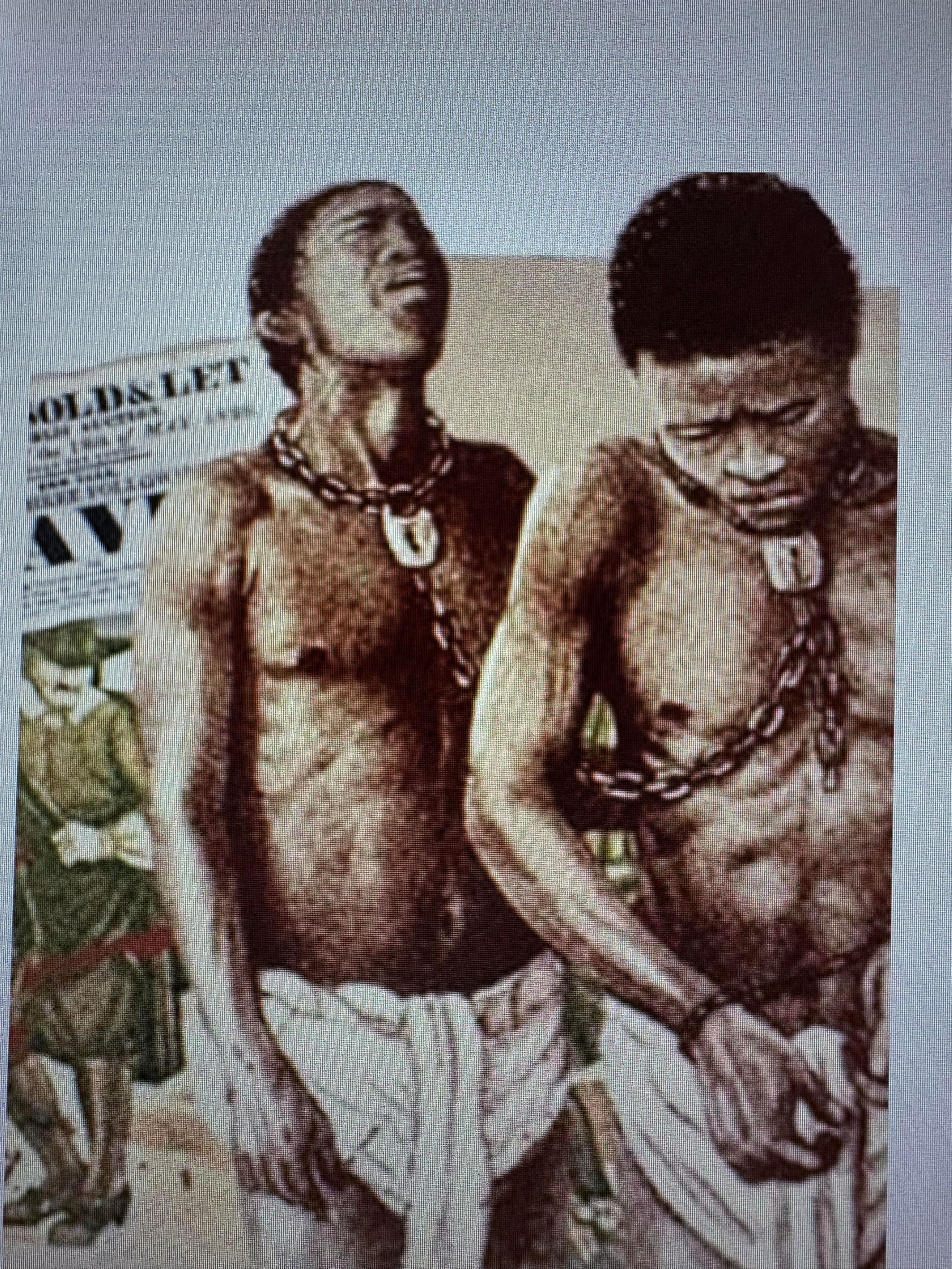

Knowledge of the past provides a firm foundation for a more just and peaceful future. My frame is that slavery is both individual and institutional sins; reparations are individual and institutional atonement. Sin is an offense that separates us from God. Atonement is the means by which sin and, its consequences are forgiven and reconciled with God; reparations provide us with this opportunity. At its simplest, reparations mean repairing a wrong that has been done; those who commit crimes against humanity are morally and legally bound to make amends. In our case, the crime is clear, the capture, sale, and trafficking of our African ancestors across the Atlantic, and their chattel enslavement in the Americas. This was not only forced labor, but it was also the stripping away of humanity, culture, and dignity.

In Grenada, the first French Catholic Dominican priest arrived in 1650, the same year as the massacre of the Kalinago people at Sauteurs, an event we must never forget. Later in 1784, the first baptisms and burials were recorded in St. George’s Anglican Church in Grenada, in the aftermath of the massacre of the Fedon rebels, who rose against slavery.

Whenever I teach Caribbean History, I begin with our Indigenous ancestors, not only out of respect, but because they are central to our story; what happened to them cannot be glossed over. It is an original sin. The prophet Isaiah, in Chapter 1, verse 17, tells us: “Learn to do right; seek justice; defend the oppressed; take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow.” In this context, Isaiah condemns religious hypocrisy. God refuses offerings from people whose ‘hands are full of blood.' In other words, worship without justice is meaningless. This should give us pause, because, when the church aids, abets, or ignores oppression, as it did during most of the period of slavery, it becomes handicapped and when the church fails to atone, it compounds the harm.

The Church as Owners of Enslaved Africans

I am not here simply to condemn the church because the story is complex. The church was also involved in the abolition of slavery and, today, many congregations, including yours, are seeking truth and reconciliation; but we cannot look away from the institutional sins of the past. Many branches of the church did not just witness slavery; they participated in it. The Anglican and Episcopal churches in Virginia, for example, owned enslaved people as institutions. Enslaved laborers worked church-owned lands and sometimes were rented out to parish ministers.

These 'institutional slaves' were often worse off than those owned by individuals because those who controlled them had no long-term interest in their well-being. The Episcopal Church in the United States and its sister Church of England in the Caribbean, were built with wealth created from slavery. The Codrington College in Barbados was funded by the profits of two sugar plantations bequeathed to the church. On those plantations, enslaved Africans were branded with the word “Society,” because they belonged to the church’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.

The "Business” of Chattel Slavery

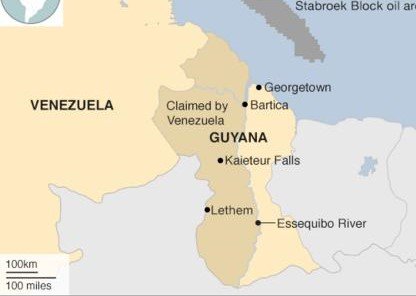

The Codrington plantations generated an estimated £5m a year in today’s money and covered 763 acres. Records show that the Archbishop of Canterbury approved funds to buy enslaved people in the British settler colonies in the 18th century. Slavery was also interwoven throughout settler colonial societies. In November of 2023, it was found out that the Insurance Company giant Lloyd’s of London, had a portfolio that was part of “a sophisticated network of financial interests and activities" that made transatlantic slavery possible. Research commissioned in 2020 found that John Edward Taylor, the journalist, and cotton merchant who founded the Manchester Guardian in 1821, had at least nine of his 11 backers who had links to chattel slavery. The Bank of England revealed new research in an exhibition in 2022, that it had owned 599 enslaved people in the 1770’s after taking possession of two plantations in Grenada.

The Scriptures were also used and twisted to justify oppression; after emancipation, Black congregations often faced discrimination within white-led Episcopal churches. Reparations are not only about money but about truth, justice, and repair. Globally, this is recognized as a debt; the United Nations has declared this as the Decade for People of African Descent, with the theme, “Recognition, Justice, and Development.”

CARICOM’s 10-Point Plan

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has developed a 10-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice, some of the demands are: A full formal apology; development for Indigenous people; repatriation; building cultural institutions; public health investment; education and literacy; African knowledge programs; psychological rehabilitation; technology transfer and debt cancellation. CARICOM’s 10-point Plan seeks justice from 11 European countries – France, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, and Norway.

These demands are not fantasies. They are researched, debated, and supported by evidence, such as the recent Brattle Report, which calculated the economic costs of slavery to our nations; one of the realities of chattel slavery is that it was a business. So, there are a lot of evidence through receipts, ledgers, court records, etc. to substantiate these economic costs. Some nations have taken steps in attempting to atone for the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Chattel Slavery; The Netherlands and Belgium have offered apologies, and Britain has offered “expressions of regret," but not a formal apology. To us, reparations is not pity or helplessness or us being welfare “queens and kings.” Transatlantic Slavery was characterized by the profound and ubiquitous resistance of the enslaved, through slave uprisings and rebellions. Caribbean and African countries have been striving for development, individually and collectively against great odds, but we are talking about a stolen legacy and stolen wealth. The church cannot undo the past, but it can speak truth, seek justice, and act with courage. By acknowledging its complicity, committing to repair, and standing with movements for justice, the church can live out the gospel. These are not easy conversations, but they are holy ones.

An African ritual being performed outside the St. Paul's Church - Photo: Keisha-Gaye Anderson

Share with your network